Street Haunting: London at Twilight

On the 'flâneuse' of Virginia Woolf's 'Street Haunting' (1927), theatricality and flirtation, and Marianne von Werefkin

In 1940 Virginia Woolf came up to London and walked round the bombed-out ruins of the Bloomsbury square where she’d lived. ‘I cd just see a piece of my studio wall standing’, she wrote in her diary – ‘otherwise rubble where I wrote so many books. Open air where we sat so many nights, gave so many parties’. Woolf spent the Blitz living in Sussex with her husband, but felt London’s devastation very personally. The city was one of the loves of her life, especially Bloomsbury; she’d moved there from Kensington, aged 22, in 1904.

I like the parallelism in that diary entry between ‘wrote so many books’ and ‘sat so many nights’, the rhythmical identity of the phrases, as if to suggest the completely symbiotic relationship of living and writing, nights of contemplation and mornings of creation, the material London of the writer’s room and her created world on the page. If a digital Blitz, a massive cyber-attack (of the kind that hit the nearby British Library in 2023) destroyed the great scattered archive of writing about London, the single work I’d most want to save is Woolf’s 1927 essay ‘Street Haunting: A London Adventure’. Every time I go back to it I discover something new, and this is what the essay’s about: the liberating sensation of being surprised.

The essay follows a quest to buy a pencil, but really this is just an excuse – ‘no one has perhaps felt passionately towards a lead pencil’ – to go for a walk. The ensuing wander across central London, south from Bloomsbury towards Oxford Street, the eastern fringe of Soho, and a glimpse of the Thames near Charing Cross, takes place between four and six on a winter’s evening. (On this June night, I’m writing once again out of step with the seasons, about an imaginary walk through the ‘champagne brightness’ of winter air; but June, and the idea of being in two places at once, make an appearance.) The essay pauses three times: at a boot shop, where a ‘dwarf’ is trying on shoes; at a second-hand bookshop; and finally at a stationer’s off the Strand, for the pencil.

‘Street Haunting’ is often discussed as a classic of London’s nightwalking literature. I think this only half-works, as a classification. Night has fallen in the sense that the sun has gone down, leaving ‘long groves of darkness’, revealing the hidden and still under-acknowledged quietness of central London, perforated by pristine squares. But the streets are full of life, hosting a ‘vast republican army of anonymous trampers’. Central London in 1927, unlike today, was a place where ordinary people lived. At teatime it throngs with activity. In glimpses of offices, ‘fierce lights burn over maps’; finishing work, people run errands before they travel home. This is a text not so much of nightwalking as of twilight, as Peter Davidson proposes in his excellent The Last of the Light (2015). When we talk about the night we often conflate three related but distinct things: the period of literal darkness; the cultural time of rest and recreation after work (in theory) ends; and the hours of our sleep. We pay oddly little attention to the way these categories overlap, and the fluctuation of that overlapping – especially in winter, when it gets dark before we stop working, and long before we go to sleep. We have no idea (as Davidson suggests in another book) how far north we live.

The essay is narrated in the first person plural: ‘we step out of the house’. ‘We’ is a delightfully fluid designation. Sometimes Woolf seems to mean a capacious notion of herself, of Me Myself and I (‘we halt at the door of the boot shop’). But sometimes ‘we’ implies ‘you, the reader, with me’, forming a conspiratorial double act (‘let us dally a little longer’), and sometimes she is speaking for all of us, a whole common society (‘here we find anchorage in these thwarting currents of being’). The essay’s gambit is that to walk the city streets is to experience a temporary expansion of the self: leaving the ‘wrinkles and roughnesses’ of a particular ego, the walker becomes ‘a central oyster of perceptiveness, an enormous eye’, and can flirt with the alternative selves and lives of which it’s afforded fleeting prospects. ‘At the antique jewellers’, the sight of a pearl necklace launches a fantasy of stepping out onto a balcony in Mayfair, late on a summer’s night, overlooking the houses of ‘great peers returned from Court’, watching ‘the moonlit cat creep along Princess Mary’s garden wall’. Who, Woolf asks, is the true self – ‘this which stands on the pavement in January, or that which bends over the balcony in June?’ It’s so beautifully, stylishly airy. But as Lauren Elkin says in her study of the flaneuse, the woman who walks the city, it’s a political claim – a woman asserting her right to the same anonymity, the same free expansion of the self, the kind men enjoy, beyond the self’s normal tramlines. In Woolf’s The Years (1937), a young Rose Pargiter sneaks out to explore the neighbourhood. Later in life, as Elkin observes, suggesting a link with her childlike desire to walk, Rose becomes a Suffragette.

Reaching the Strand, the narrator witnesses the crowd of commuters heading towards Charing Cross, and wonders what fantasies they are ‘wrapt’ in during ‘this short passage from work to home, now they are free from the desk’:

They put on those bright clothes which they must hang up and lock the key upon all the rest of the day, and are great cricketers, famous actresses, soldiers who have saved their country at the hour of need. Dreaming, gesticulating, often muttering a few words aloud, they sweep over the Strand and across Waterloo Bridge…

This is a slice of freedom, and the language is full of briefly liberated agency as the commuters ‘sweep over the Strand’. It’s only fleeting, as once they get to the station they become passive again, and ‘will be slung in long rattling trains, to some prim little villa in Barnes of Surbiton’. We hear clearly the note of condescension towards the workers of the world. But in the previous sentence we also enjoy Woolf’s generosity towards the commuters, the seriousness of their fantasies, however childlike. (Maybe these two attitudes, condescending presumption and affectionate generosity, come together; maybe the risk of our current taboo on any kind of presumption is that we remain very incurious and afraid of one another.) In 1927, this crowd includes working women, but nevertheless it’s intriguing that ‘famous actresses’ rub shoulders in this sentence with ‘great cricketers’ and ‘soldiers’; even here, the mind of the city-walker moves towards the state Elkin calls ‘de-sexed, ungendered’.

The flirtatious expansion of the self which takes place in the city’s twilight is a kind of theatricality, the putting on of another life like a costume (‘those bright clothes which they must hang up… all the rest of the day’). In the boot shop, the ‘dwarf’ puts off selecting a pair as long as she can, to the annoyance of her friends, enjoying the not-choosing. The walk passes ‘the narrow old houses between Holborn and Soho’, whose inhabitants have the typecast eccentricity of the Dickensian minor character: ‘such queer names, and pursue so many curious trades, gold beaters, accordion pleaters’. Often, Woolf notes, such people live ‘not a stone’s throw from theatres’.

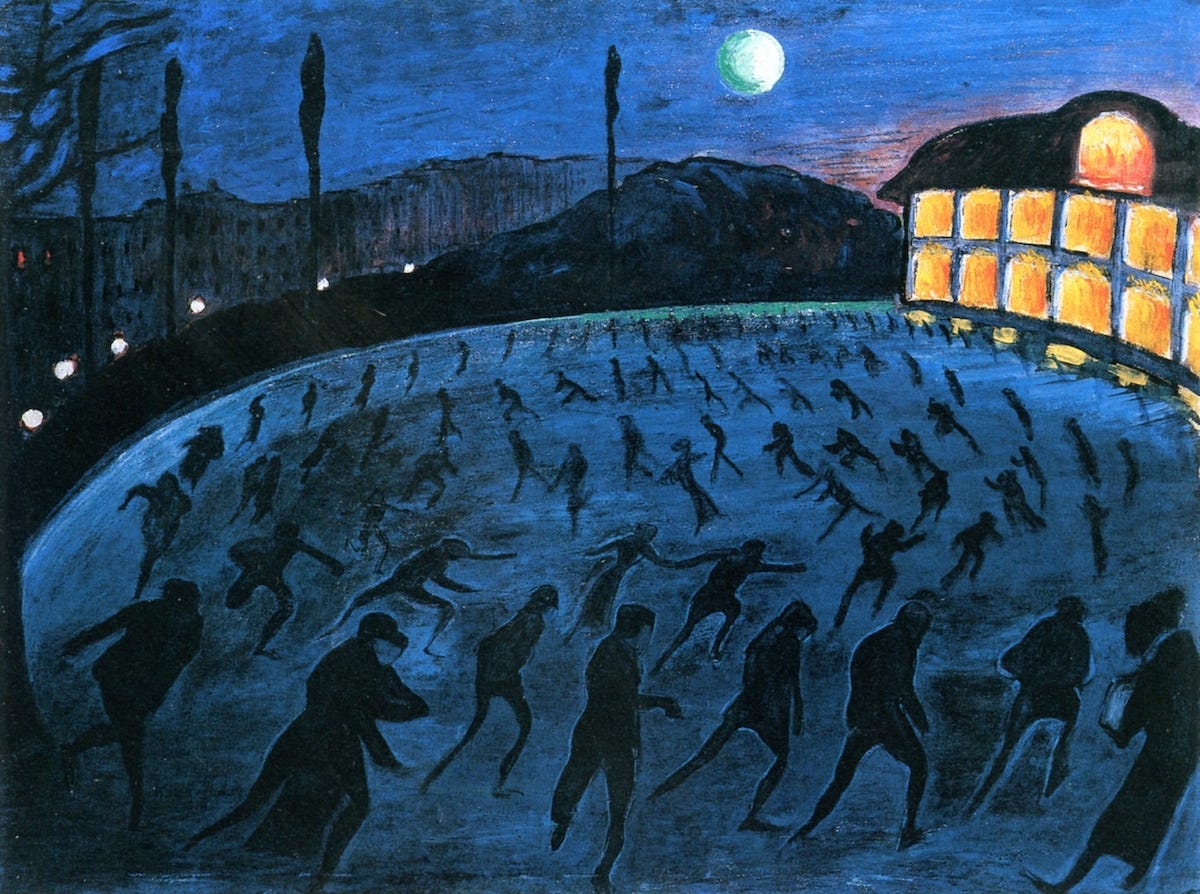

This year’s exhibition of the expressionists in the circle of Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter included paintings by Marianne von Werefkin, and they made me think of ‘Street Haunting’. In Werefkin’s Munich, like in Woolf’s London, early evening is the natural time for dressing-up, for the theatre. ‘Into the Night’ (1910) depicts a lamplit little square opening from an alley; squashed into the foreground, a crowned king confronts a figure in a cloak and plumed hat; the audience’s benches are empty but, huddled in doorways across the square, two women are watching. In ‘Skaters’, the moon is dwarfed by the huge circle of an urban ice rink, lit by the galleries of an overlooking palace. The dark blue rink hosts a ‘vast republican army’ of skaters, and this time the release is not so much the flirtation with a single alternative self, the putting on of the king’s or actress’s or cricketer’s role, as the liberation from any particular role at all: the skaters become nothing but pure bodies, black silhouette moving over the ice, the somatic equivalent of Woolf’s smooth and anonymous ‘oyster of perceptiveness’. Did Woolf ever see Werefkin’s paintings?

The pencil is bought, from the married couple who own the stationer’s and who we intruded on, mid-argument. We turn out into the street, finding that this twilight zone of theatrical flirtation is over. ‘The streets had become completely empty… the pavement was dry and hard; the road was of hammered silver’. All that remains is to walk home, carrying the pencil, ‘through the desolation’. The essay finishes with a glimpse at a different temporal and spatial zone, of walking the city after the withdrawal of quotidian life from its streets. In the province of true nightwalking, there are fewer cues for trying on different selves. Who would you meet out in the late deserted night, except yourself, stripped from all comforting roles and liberating, temporary performances?