Strangeness and Intimacy: Hammershøi's 'The Coin Collector'

Thoughts on a night scene by the Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi, and why night makes us better at being strangers...

I don’t know whether the Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi had a habit, like Peter Doig, of painting at night. But one Hammershøi painting, which I’ll explore here, seems to speak (quiet) volumes about nocturnal life in modernity. It feels disconcerting to write casually about Hammershøi, because Rainer Maria Rilke studied his work for a whole year before abandoning his attempt at capturing the ‘essence of this timeless master’. One reason Hammershøi is difficult to write about is that nothing much is ever happening in his paintings: landscapes and interiors stripped of narrative, quiet and still, full of mystery. In a poem called ‘The Landscapes of Vilhelm Hammershøi’, Vona Groarke compares their enigmatic feel to ‘water reading itself a story / with no people in it’.

‘The Coin Collector’ is one of four Hammershøi paintings hanging in the National Museum in Oslo. It dates from 1904, when Hammershøi was forty; in 1891 he had contributed to the foundation of Den Frie Udstilling, an association for artists unacknowledged by the Danish Royal Academy. He travelled widely, but Copenhagen was always his home, and ‘The Coin Collector’ depicts an apartment he owned on Strandgade, and which he painted obsessively.

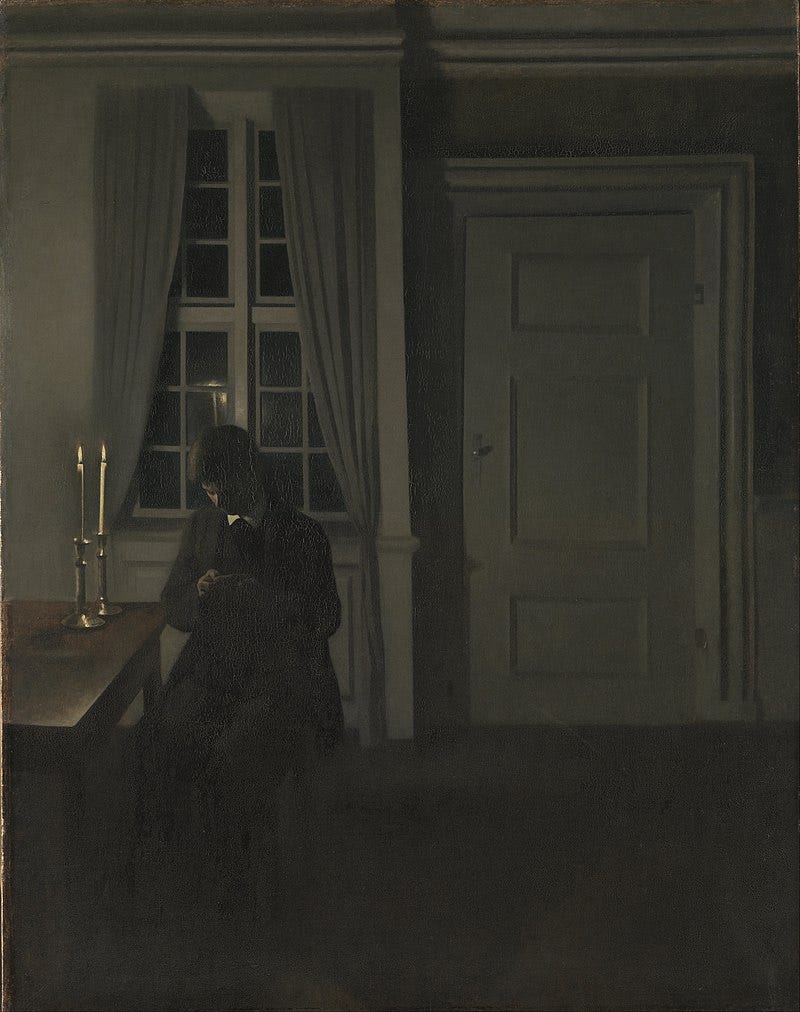

(Hammershøi, ‘The Coin Collector’, 1904)

Here is a man alone at night, absorbed in silent and solitary activity. He has placed the pair of candlesticks together, to illuminate whatever he is turning over in his hands. At a communal table candlesticks would usually be spread out; now that sociable light is gathered in. The candlesticks echo in the dark window behind the man, and Hammershøi renders that reflection without much distortion. For a moment we might feel that there’s another source of light in the painting, coming from outside. But that briefly suggested exterior presence is illusory, a phantom, just like our own exterior presence, looking into a world of which we are not fully part.

Apart from the man, the room features an assortment of rectilinear forms – the window subdivided into panes; the skirting board and the table’s edge – invested with an uncannily lifelike quality. The white door looms, with its three shadowy recessed panels slightly suggestive of head, torso and feet. Hammershøi’s apartment on Strandgade, in a seventeenth-century district of Copenhagen noted for its quietness, happened to include many doors. (A diagram of the apartment that appeared in an old exhibition catalogue suggests the number is twelve or thirteen.) ‘White Doors’, from 1899, depicts a cluster of entrances and exits, opening on the wooden floorboards of austere rooms and closing off others. The open doors stand at angles to the rectangles of the rooms and their own frames – as if the doors, not the dwellers in the house, are the occupants. In ‘Study in Sunlight’, similarly devoid of human figures, the same door that appears in ‘The Coin Collector’ is shown without its handle. Hammershøi accentuates the enigmatic solitude of his human figures by endowing their domestic surroundings with a strange, rival presence. Foreground merges or melds with background. At night, these ordinary features of a domestic interior emerge into a new prominence, shrugging off their everyday functions: like the white door losing its handle the window, which is meant to let in light, becomes another enigmatic surface, a blank pattern of black panes.

Bridget Alsdorf, in an essay on the Strandgade paintings, notes that ‘The Coin Collector’ is one of only a few in the series to depict the apartment at night. She contrasts this portrait, in which ‘inwardness is absolute’, with the many scenes of Hammershøi’s wife, Ida, engaged in ordinary life. In those paintings Ida’s absorption – playing the piano, clearing up the cups, staring through the window – prevents us from seeing her fully, as she turns her face away from us and towards the object of her contemplation. For Alsdorf this enigmatic quality is beautifully offset by the intimacy of what is happening, and the ordinariness of diurnal light. She compares this balance to Kierkegaard’s defence of a good marriage as a supreme reconciliation of ‘aesthetics’, standing here for mystery and longing, with life.

But ‘The Coin Collector’ achieves a different balance of intimacy and enigma – and that balance applies, perhaps, more generally to the modern experience of night. We look in on a person we don’t know, and our gaze is unromantic: unlike Kierkegaard’s young lover, we aren’t staring with particular attention at someone significant, and whose true essence continually eludes our fixation. We look at this scene the way we glance through a window while walking the city after dark: fleetingly, furtively, and without background knowledge. And because at night, as Alsdorf suggests, ‘inwardness is absolute’, it’s impossible to gain any access, or any hint of access, to the person we see. But there’s a paradoxical intimacy to this gaze, I think, which could be generalised as the paradoxical intimacy of night vision. By making both ourselves and our surroundings appear strange, the night removes any pressure or expectation to conquer the enigma, to get to know each other. It’s an instance of the intimacy experienced between strangers who are happy to remain strangers.

The man in this painting is Svend Hammershøi, the artist’s younger brother. Svend had a significant artistic career of his own, outliving Vilhelm and travelling for many years to England, where he painted scenes of London and Oxford, often with a mysterious golden glow. His vision is more precise and less mysterious than his brother’s – it captures the miraculous hardness, rather than the softness, of northern European light.

(Svend Hammershøi, ‘The Clarendon Building, Oxford’, c.1925)

Svend is relaxing, here, by examining his coin collection. He peers at what might be an album on which his coins are mounted. Alsdorf observes that Hammershøi typically blurs objects of contemplation: in his ‘Interior with Woman at Piano’, Ida faces away from us, beyond a table where a bright pat of butter stands on a table otherwise empty of food; but unlike the butter, the sheet music and the paintings hanging above Ida’s head are abstracted, washes of white and grey. That blurring says something about the elusiveness of people when they are absorbed, but also about the nature of contemplative activity itself, its ability to transport the mind through the activity – playing the piano, for example – to somewhere else.

If we are lucky, we have spaces in our lives for contemplation, or for contemplative, absorbing activity in which we can reclaim some of our focus and our identity. Some of these activities, like Peter Doig’s racquetball, take place in a social sphere; some match the natural tendency of the night towards solitude. Bruce Chatwin’s Utz (1988) tells the story of an obsessive Czech porcelain collector, who creates in his cramped Prague apartment a disconcerting alternative world of Meissen figures – an alternative reality rather like the ones we sometimes stumble on at night. (Utz’s pursuit of the figures also blinds the novel’s narrator to his vigorous seduction of real – within the fiction, at least – opera singers.) A hobby like coin collecting veers oddly close to everyday life, under modern capitalism, and some of its typical nightly aftershocks: working all day to make money, and worrying about how much you have that evening. Despite this, Svend seems wrapped up in a better state than money worries: he’s collecting himself.